In the Trenches: How Not to Troubleshoot in Mold Repair

In mold repair “really important” refers to correcting problems, not just working around them.

Remember last month’s “The Trouble with Troubleshooting” article? Well, it is with mixed feelings that I write about a lesson learned in the School of Hard Knocks, because it doesn’t depict me as the genius I always wished I were. Years ago, I read “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” and my takeaway was an understanding of the struggle between the urgent and the important, and of how we often respond to urgency at the cost of ignoring what is really important.

Really important in mold repair refers to correcting problems and refraining from getting in the habit of just working around them. However,when production and deadlines are at stake, getting parts out the door is both urgent and important. I guess the trick is to not allow the workaround to become the standard M.O.

Finding the Culprit

So, my sad tale from the School of Hard Knocks that illustrates how not to troubleshoot runs like this:

There once was a simple part formed by a simple mold, but the part had an inordinately high scrap rate from contamination. Odd, since it was a new tool and fed only the best virgin resin.

So from where did the contamination come? I wish I had a concise and complete answer for you, but the truth is, as much as I believe in and preach the message of data collection and data-driven maintenance, my records were still inadequate.

About five months into the life of this tool came the first indication that something was amiss. The mold started “popping” when it opened. This meant that, due to thermal expansion or insufficient lubrication, the die lock surfaces were binding up when the mold clamped shut and they required excessive force to break loose when the mold opened. This popping was (or should have been) a hint that the die locks were an issue.

This was a new program launch. The fact that the first indication of trouble didn’t show up until five months after the tool was received indicated that this may have been closer to the start of production (SOP) date and that the previous runs had been sporadic and low-volume. Also unknown was whether there were process changes that may have affected the temperature between the mold halves.

Keep in mind that a truly robust mold history system would include all information that may be pertinent to a mold’s functionality (i.e., SOP date, engineering changes, process changes, work performed by an outside vendor, etc.).

After another two months, we started having intermittent issues with the appearance of the part such as water spots or haziness. We now had a defect that was identifiable and repeatable in frequency if not location, so it received a name: contamination.

Although we had experienced contamination before, this was chronic contamination, so it became a new part defect entry in the work order database. The usual suspects for contamination are resin and leftover material not completely purged from the barrel.

In this case, resin was not the culprit because it was 100-percent virgin material out of the same silo that fed a dozen other presses without causing contamination issues. Leftover material also was not the culprit because this press had not run anything but ABS in 12 years. So the contamination had to be coming from the tool.

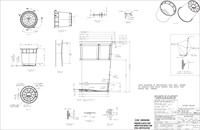

Looking at the parting line, it didn’t take long to find the source of the contamination (see illustration on page 35). A large bathtub lock above the cavity showed signs of galling. (The die lock issue should have been a hint of impending trouble.) Fine gray dust covered the locking surface. Cleaning this out should have corrected the problem—and it probably did the first few times—but the problem persisted.

Seemingly Simple Solutions

Sadly, and to no one’s fault other than mine, a classic case of “Band-Aiding” or “putting up with” had become the standard mode of dealing with this particular mold. Sure, a few suggestions were offered and considered, but cost or implementation challenges prevented us from doing anything substantive to correct the problem.

Our initial solution was to implement a regular routine of parting line cleaning (which also became an added descriptor in the work order database). This reduced scrap and downtime, but it did not completely eliminate them. We headed off most of the scrap, and when things started to go south during the run, at least we went to the press knowing what to do rather than looking for the cause.

One of the first suggestions for correcting the problem was to flip the mold 180 degrees. As can be seen in the illustration (page 35), the cavity’s orientation creates a shelf that catches falling debris.

Rotating the mold 180 degrees would put the cavity above the source of contamination, eliminating the scrap issue. However, our molds are mounted on quick-mold-change plates, so flipping the tool involves more than simply loading it upside down in the press. It means rotating the mold on the clamp plates, which, in this case, are integral parts of the mold. This option would be time-consuming and costly, so it was dismissed—perhaps way too quickly.

Another idea was to add an air blowoff to the robot so that as it retracted from the press, air would blow debris off the cavity shelf. This seemed like a fairly quick, cheap and easy modification, so we went with it. This, too, (in addition to the regular parting line cleaning) was effective at reducing scrap. Although this option was nothing to be especially proud of, when you’re frustrated and lacking a perfect solution, you’ll go with what works.

Summary

At this point in the story there are three lessons learned:

1. Good troubleshooting begins by not ignoring the signs of impending problems. For example, further investigation of the mold that started popping to determine whether it was a thermal or lubrication issue.

2. Troubleshooting depends on correct, accurate and definitive information. Avoid catch-all phrases such as “appearance issues.” Call it what it is!

3. Do the hard stuff. Don’t be too quick to dismiss suggestions just because they are difficult to carry out.

Although this saga is far from finished, we have progressed from reactions to responses, which do inevitably yield better results. Next month we will continue with this troubleshooting tale by examining additional problems and signs, and a final resolution.

Related Content

What Is Scientific Maintenance? Part 1

Part one of this three-part series explains how to create a scientific maintenance plan based on a toolroom’s current data collection and usage.

Read MoreWhat is Scientific Maintenance? Part 2

Part two of this three-part series explains specific data that toolrooms must collect, analyze and use to truly advance to a scientific maintenance culture where you can measure real data and drive decisions.

Read MoreWhat You Need to Know About Hot Runner Systems and How to Optimize Their Performance

How to make the most out of the hot runner design, function and performance.

Read MoreQuestions and Considerations Before Sending Your Mold Out for Service

Communication is essential for proper polishing, hot runner manifold cleaning, mold repair, laser engraving and laser welding services.

Read MoreRead Next

In the Trenches: Mold Repair

In this multi-part series of articles, contributer James Bourne, a tool repair supervisor and freelance writer, shares his own personal struggles in the business, as well as lessons learned and tricks of the trade garnered along the way.

Read MoreHow to Use Strategic Planning Tools, Data to Manage the Human Side of Business

Q&A with Marion Wells, MMT EAB member and founder of Human Asset Management.

Read MoreHow to Use Continuing Education to Remain Competitive in Moldmaking

Continued training helps moldmakers make tooling decisions and properly use the latest cutting tool to efficiently machine high-quality molds.

Read More