New Talent, New Services Build on Solid Foundation

At Superior Tooling, scientific mold sampling is a natural extension of a scientific mold manufacturing process. Meanwhile, the company is more excited than ever about a new apprenticeship program.

Superior Tooling appeared in this space exactly one year ago, but the primary focus of that article wasn’t the shop itself. It was the North Carolina Triangle Apprenticeship Program (NCTAP), which the Raleigh-based mold manufacturer joined as a founding member in late 2013. Now entering its second full year, the program is attracting more attention than ever, including from the highest levels of government, says Robbie Earnhardt, company founder and president.

Participation in a program like NCTAP isn’t the only reason to take a closer look at this forward-thinking mold manufacturer. Earnhardt and his team believe that a competitive future will require incubating not just the skills required to produce quality tooling, but also the right processes for running that tooling in customers’ injection presses. Opened just last fall, the company’s technical center is dedicated to that purpose.

Yet, these efforts can’t be divorced from their broader context. Superior Tooling’s core business is manufacturing molds, and the shop continues to pursue improvements here as well. This evolving approach to production both influences and is influenced by recent efforts in tool qualification and workforce development.

Going Scientific

Injection molding capability isn’t completely new to Superior Tooling. The company had been running sampling cycles on 100- and 200-ton hydraulic presses at its main shop for a decade before moving the two machines to the new technical center (it’s since sold the latter machine). Now, however, capabilities are far more robust.

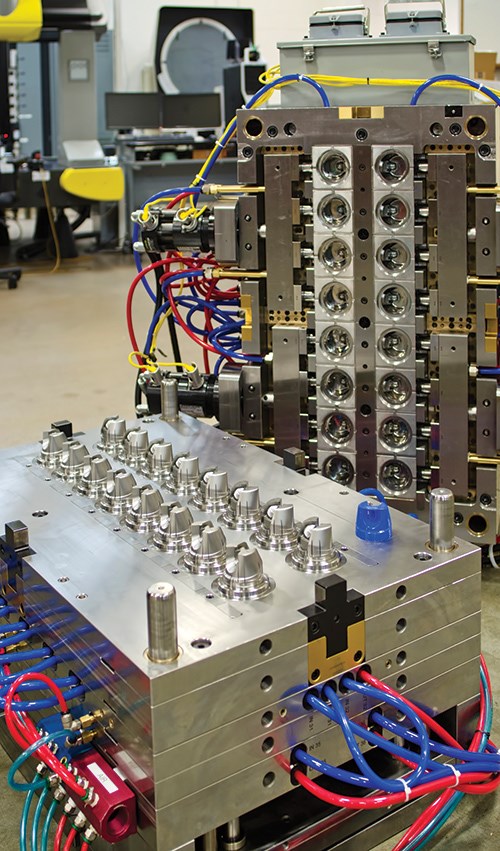

Superior’s third press, a recently installed, 320-ton model from Negri Bossi, offers more than just capacity for a wider range of tool sizes. Its all-electric configuration makes it a better equivalent to equipment used by customers, and it provides more data about the process. Along with a newly hired plastics engineer who oversees these operations and various supporting technology (temperature controllers, metrology instruments and so forth), this facilitates a value-add that goes beyond just testing for fit and function. “In the past, we’d just make sure the plastic would fall out, and that was pretty much the extent of it,” Earnhardt says. “Today, customers want gate studies, water flow analysis, different process conditions. They want us to help dial in the process.”

That means measuring and documenting everything. Plastic material viscosity and shear rate, water pressure and turbulent flow, packing pressures—finding and testing for the correct values requires following predetermined processes to the letter, with little room for individuals to do things their own way. Tools must be adjusted to fit the customer’s process, not the other way around. There can be no on-the-fly parameter tweaks to make the process work.

This transition to more scientific sampling was a natural extension of a transition to a more scientific production process on the shop floor. As is the case with sampling, few critical decisions are left to individuals. Rather, the entire manufacturing process for any given job is worked out in advance in a team setting. Proper execution depends heavily on five-axis machining centers, pallet systems, robotics, standardized workholding and other technology that limits human intervention, thus avoiding levels of variation that are simply no longer acceptable. Time, cost and other metrics are thoroughly documented at each stage of the build. Mistakes are rarely repeated, and best practices are incorporated into future jobs.

Increasingly, these best practices result from issues detected during tool qualification. Examples range from ergonomic improvements, such as eliminating sharp edges that might nick a press operator’s finger, to functions that affect how the tool runs, such as the orientation of conformal cooling lines. These benefits extend both ways, Earnhardt points out. Just as more scientific sampling contributes to better toolmaking, a more scientific production process helps ensure molds run right the first time.

Training to a Culture

Adopting a more scientific process has required significant investments in new equipment on both sides of the operation, but technological change isn’t enough by itself, Earnhardt says. For Superior Tooling, cultural change has been just as important. “You can’t think of a mold as a piece of art that one person builds,” he explains. “You have to drive it through the shop like a production item.”

This change in thinking has been evolving for more than a decade at the company, Earnhardt says, and he expects involvement in NCTAP to accelerate it. After all, apprentices start while they’re still in high school. At that age, they’ll bring none of the preconceived notions that might come with a more experienced new hire. “We’re going to be developing a new generation of toolmakers here, and we can groom them to our process,” he explains. As an example, he cites an apprentice the company hired a few years ago, prior to its involvement in NCTAP. “He leaves here at the end of the day with the robot full of electrodes and ready to run all night. He really gets it.”

However, grooming people to a process requires putting that process in place first. Earnhardt says his own apprenticeship decades ago would never have prepared him to work at Superior Tooling today. Back then, the goal was to train employees in all aspects of building a mold. Given the sophistication of modern technology, that’s much more difficult today. Moreover, an approach that treats a mold more like a production item than a piece of art is more effective when each employee is a specialist in his or her particular area. That’s why incoming apprentices undergo structured training that helps them move toward specific areas where they show the most promise and interest. At the time of this writing, for example, the aforementioned apprentice was transitioning from running sinker EDMs to a specialty in milling the electrodes. “We find what they’re good at and what they want to do, and we work them in that direction,” Earnhardt says.

Building a Pipeline

NCTAP’s promise of a steady stream of apprentices to train in this manner hasn’t come to fruition yet. In the program’s first year, Superior Tooling didn’t accept any candidates. However, Earnhardt stresses that this outcome wasn’t unanticipated. For one, the program has a rigorous application process. That includes initial shop tours to gauge interest, an orientation session to gauge aptitude and summer internships to gauge performance before full acceptance into the four-year-long program, which begins in the student’s senior year of high school. Weeding out all but the most promising candidates is important, given that the company might invest as much as $150,000 in each potential hire’s salary and tuition for part-time coursework at Wake Tech Community College. “It also takes some time for an effort like this to grow wings,” he adds.

Judging from recent developments, NCTAP could take flight for Superior Tooling sooner rather than later. For one, members have received a number of letters from interested candidates—something that didn’t happen last year—and initial orientation sessions attracted far larger crowds. Perhaps more notably, some of the aforementioned letters came from parents, who are often more difficult to educate than their children about the benefits and the nature of modern manufacturing careers, Earnhardt says. Although the same goes for educators, NCTAP partners have been invited to present to guidance counselors at more than 40 local high schools this year, more than double the amount of last year.

Finally, NCTAP has attracted attention from the White House, which recently announced $100 million in grants for apprenticeship programs. After a meeting with Secretary of Labor Tom Perez, Earnhardt and other members are optimistic that the program may see some of that funding. Whatever the future holds, such attention is certainly a positive in Earnhardt’s mind. He last visited Washington, D.C., more than 6 years ago to push the need for solutions to the shortage of qualified employees in the trades—a message that fell on deaf ears, and not for the first time. “It’s been going on 12 or 13 years that I’ve been trying to push this thing, and it was going nowhere,” he says. “Everyone said we’d be a service economy; that we wouldn’t have to make anything. People are finally starting to wake up.”

Related Content

How to Use Continuing Education to Remain Competitive in Moldmaking

Continued training helps moldmakers make tooling decisions and properly use the latest cutting tool to efficiently machine high-quality molds.

Read MoreMaking Mentoring Work | MMT Chat Part 2

Three of the TK Mold and Engineering team in Romeo, Michigan join me for Part 2 of this MMT Chat on mentorship by sharing how the AMBA’s Meet a Mentor Program works, lessons learned (and applied) and the way your shop can join this effort.

Read MoreTackling a Mold Designer Shortage

Survey findings reveal a shortage of skilled mold designers and engineers in the moldmaking community, calling for intervention through educational programs and exploration of training alternatives while seeking input from those who have addressed the issue successfully.

Read MoreMMT Chats: The Connection Between Additive Manufacturing Education and ROI

This MMT Chat continues the conversation with Action Mold and Machining, as two members of the Additive Manufacturing team dig a little deeper into AM education, AM’s return on investment and the facility and equipment requirements to implement AM properly.

Read MoreRead Next

A Proven Model for Apprenticeship

Steve Rotman, president of Ameritech Die and Mold, sheds light on his experience as one of the founding members of an apprenticeship program that has been churning out skilled workers for his shop and others since the mid-1990s.

Read MoreTapping into Talent

Seven North Carolina manufacturers—including one moldmaker—hope to build their future workforces through European-style apprenticeships.

Read MoreHow to Use Continuing Education to Remain Competitive in Moldmaking

Continued training helps moldmakers make tooling decisions and properly use the latest cutting tool to efficiently machine high-quality molds.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)