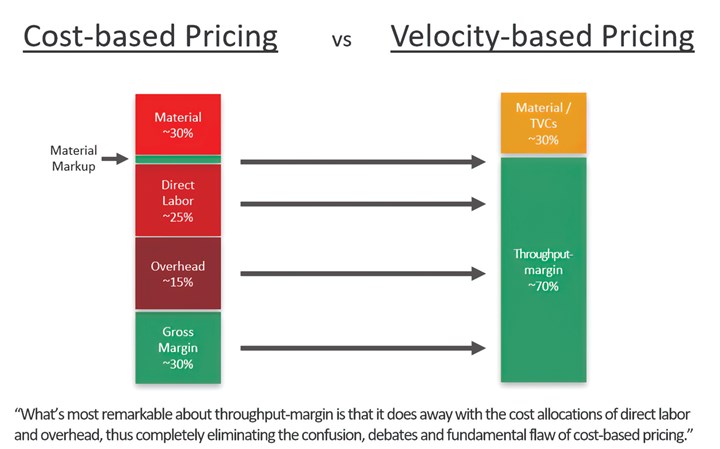

Whether you’re using cost accounting, activity-based costing, standard costing, lean accounting or any other costing method, costing is driving your pricing.

It’s hard to make money consistently. Being in the moldmaking industry, you’re well aware of the standard mode of operation: feast or famine. Even worse, it feels like despite how busy you may or may not be, there’s never enough money making its way to your bottom line (and into your bank account). Even during feast times when revenues are up, many shops don’t see as much drop to their bottom line as they would like or would have expected. But in either case, feast or famine, a common thread lies at the center of both your sales level and your profitability: pricing.

Do you lose opportunities because your price is too high? Do you ever feel you might be leaving money on the table? Are you ever less than 100% confident in your price?

Pricing affects your revenue and your bottom line. But despite this fact, pricing receives very little attention. Instead, you may hear shop owners and managers complain, “Our cost structure is just too high to compete at these prices. We’ve got to reduce costs.”

In actuality, your cost structure probably isn’t too high. Can you reduce expenses some? Sure. The reality is that most shops are already managing their costs extremely well. Unless there’s a big, bottomless pit that you’re shoveling money into, your costs are probably in line. However, it’s this focus on cost that drives pricing.

Method to Your Madness

It’s not your costs that are the problem; it’s your costing method. Whether you’re using cost accounting, activity-based costing, standard costing, lean accounting or any other costing method, costing is driving your pricing. This cost-based approach to pricing used in moldmaking and other industries is the fundamental flaw causing your net profit to be less than 10% of sales.

“What’s most remarkable about through-margin is that it does away with the cost allocations of direct labor and overhead, thus completely eliminating the confusion, debates and fundamental flaw of cost-based pricing.” Photo Credit: Science of Business Inc.

Now you may wonder why cost-based pricing is flawed and ask after possible alternatives. Cost-based pricing, regardless of method, allocates direct labor and overhead costs to calculate a job cost, cost rate or shop rate. The idea is that if every job you sell absorbs some of your costs, then you will know at what point you are making money in order to ensure you’re covering them.

The problem is that direct labor and overhead costs do not vary by the job. Most shops do not pay employees piece rate; they pay their employees for the hours they work regardless of what is shipped—even if that is nothing.

The same is true for overhead. Overhead (manufacturing overhead) takes its name from all the costs that occur “over the heads” of workers on the shop floor. These include items like the building rent or lease expense, electric, water and other utility expenses, as well as manufacturing supervisors, IT, environmental, quality and all the other expenses related to manufacturing that are not direct materials or direct labor.

Overhead includes both fixed and variable costs, just not those directly traceable to a job. And yet, your cost-based pricing approach has you trying to trace overhead to a job. If your overhead costs are not increasing because you added a new job, why do you need to allocate these costs to that job? Or why allocate more overhead to jobs with more hours?

Cost-based pricing is allocating “costs” to jobs, even though the underlying expenses don’t change and are not in any way related to a specific job. For example, the amount of direct labor and overhead allocated to a job, the cost rate or the shop rate is usually based on annual volume/capacity assumptions and the time estimate for the job.

If you know only one thing about assumptions and estimates, it’s that they are wrong. That’s why the various methods (cost accounting, activity-based costing, standard costing, lean accounting or any other costing method) produce different answers to the job cost question. And none of them were made for the feast or famine cycle that moldmakers experience.

The various costing methods produce different answers to the job cost question, and none of them were made for the feast or famine cycle that moldmakers experience. Photo Credit: iStock

Costing Flaws

Why is cost-based pricing flawed? The answer is allocations. These allocations skew all your pricing inputs, and because there’s no one way or one right answer to allocation, you’re building on a shaky foundation. No wonder there’s disagreement on price and you have no confidence in the quote you’re about to send off!

While the accountants don’t like to admit it, if pressed, they will confess they can make any job “cost” any number you want. How can there be an agreed-upon foundation for quoting and pricing if the starting point can be so wildly manipulated? There can’t!

Another flaw of cost-based pricing is thinking in terms of job profitability. The idea is supposed to be that if every job is profitable, the company will profit. Again, it makes logical sense, but again this thinking is built on that same shaky foundation—allocations.

Job profitability or the gross profit of a job, is calculated by subtracting a job’s “cost” from the selling price. The cost of the job includes raw materials, outside processes, freight in/out and an allocation of direct labor costs based on the time estimate of the job. Job costs also include any sales commission for the job (if paid) and an allocation of manufacturing overhead costs based on the time estimate of the job.

With the concept of throughput-margin you can’t lose money on a job. Jobs don’t have profits, only companies do. Photo Credit: Getty Images

If this calculated gross profit is positive, the job is profitable. Many companies have a goal or minimum they’re trying to achieve. However, even if companies hit these profitability targets at the job level, the company as a whole may still be losing money.

It makes you stop and ask: If companies are shipping profitable jobs, why are so many so close to breakeven or 1-2% return on sales? Wasn’t the whole point of doing all those allocations to ensure that all your costs are covered? What happened?

Dissecting Allocations

Allocations distort reality. What’s worse is that they make it difficult to understand how each job contributes to overall company profitability. Job profits are not cumulative. In other words, you can not add up all the job profits to get the company profit. Therefore, it’s no wonder jobs aren’t adding up to the company profitability you expect and it’s difficult to achieve at least a 10% return on sales.

Three standard solutions to these struggles are:

- Add more detail to your allocations.

- Change to a different—presumably better—allocation/costing method.

- Automate this already time-consuming process with software.

However, none of these solutions address the fundamental flaw. Instead, they attempt to improve allocations. This is akin to improving the house on your shaky foundation.

The negatives of cost-based pricing persist:

- High complexity is involved in tracing all the costs.

- Time-consuming, detailed engineering time estimates.

- Lack of agreement on the allocated costs of direct labor and overhead.

- There is no true way to appropriately charge for value-add items, especially those without “costs” (e.g., reduced lead times).

- Losing too many opportunities or leaving money on the table.

- No confidence in the resulting quote.

An alternative to a flawed cost-based pricing approach is a velocity-based approach1.

Simply put, throughput-margin is the revenue from a job minus the raw material, outside processing, freight in/out (including packaging) and sales commissions.

Velocity-Based Pricing Approach

At the core of velocity-based pricing is the concept, throughput-margin. Simply put, throughput-margin is the revenue from a job minus the raw material, outside processing, freight in/out (including packaging) and sales commissions. It can be determined by subtracting revenue minus the total variable costs (TVCs). These TVCS are the costs you will incur because you took the job and would not incur if you did not. They vary by the job. They are known.

What’s most remarkable about throughput-margin is that it does away with the cost allocations of direct labor and overhead, and eliminates the confusion, debates and fundamental flaw of cost-based pricing.

Each job generates throughput-margin. That margin is generated regardless of how much time it takes to run the job and regardless of the accuracy of your time estimates. None of the TVCs are based on time estimates. It’s just the revenue of the job minus your expenses directly related to the job.

At the heart of velocity-based pricing is the concept, throughput-margin. Photo Credit: Getty Images

With the concept of throughput-margin, you can’t lose money on a job. Jobs don’t have profits—only companies do. Every job generates throughput-margin. Even if the job takes three times as long as you estimated, you still generate that throughput-margin. The only way to lose money on the job is to price it less than your TVCs, or purchase those TVCs multiple times because you need to rework the job.

A common question is, “If you’re not allocating costs, how do you ensure all your costs are covered?” Understanding company profitability and how jobs contribute is much easier in velocity-based pricing. Unlike job profits, throughput-margin is cumulative. All you have to do is add up the throughput-margin you generated in the period and subtract your operating expenses for the same period and you will arrive at your net profit.

Operating expenses (OE) are all the costs that are not TVCs. They include direct labor, salaries, rent, utilities, shop rags, insurance, IT and all other costs except raw material, outside processing, freight in/out and sales commissions. OE does not vary by the job. If you take one more job, OE does not change. That’s not to say OE can’t increase or decrease. If you double sales, OE may need to go to a new higher level. You typically know your OE for the month, except for any increase you might need in direct labor for overtime.

Enter Pricing

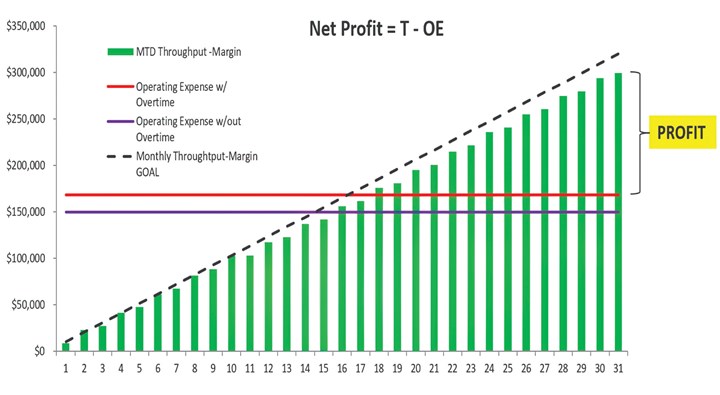

With these two cost categories, you can easily track and understand your company’s profitability and see how each additional job you ship contributes. Shown in the graph below, the green bars depicted over the red line is your profit for the period. Profit is simply the cumulative throughput-margin minus the operating expenses (including overtime). The trick is to ensure that the velocity of throughput-margin generated is sufficient to cover all operating expenses and make a profit. And this is where pricing comes in.

Profit is the cumulative throughput-margin minus the operating expenses, including overtime. Photo Credit: Science of Business Inc.

Revenue or quoted price = TVCs + throughput-margin. Since TVCs are known, the question is: “What should the throughput-margin be?” The answer depends on your “shop parameters,” which are all things that encompass your capacity, capabilities, operating expenses, productivity and uniqueness. Based on these parameters, you can determine a minimum amount of throughput-margin you need to be above break-even and what’s needed to generate the desired profit level for the company.

The key to velocity-based pricing is that it’s a system.

That job’s “special circumstances determine any specific job that falls within that range.” This is where you take in the whole situation, including customer, competitive landscape, payment terms, etc. These special circumstances are used to dial in the throughput-margin with a high probability of winning the work while not leaving money on the table.

The key to velocity-based pricing is that it’s a system. While you start with a range, the quoted price is dialed in for the specific job. It’s not the wild west. There is a discipline that creates an opportunity to align operations with the quoting process. You can’t always increase price; some of your profitability needs to come from productivity improvements. If you align quoting and operations, the velocity of throughput-margin that can be achieved is upwards of 10% return on sales.

A velocity-based approach has several distinct advantages:

- Speed and simplicity.

- No cost allocation is required.

- The need for time estimates can be reduced or eliminated.

- Mechanisms exist for appropriately pricing value-added items.

- There is confidence in the throughput-margin being earned from each job.

- It’s clear how to make more money without having to raise prices.

There’s no question that determining the price you will quote for each job is one of the most critical strategic and tactical activities in which moldmakers must constantly engage. It’s not discretionary. It’s not an option. It’s crucial. Your profits depend on it!

Reference

1 In 1998, Brad Stillahn developed the Velocity Pricing System approach as the owner of a custom job shop.

Related Content

MMT Chats: Solving Schedule and Capacity Challenges With ERP

For this MMT Chat, my guests hail from Omega Tool of Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin, who share their journey with using enterprise resource planning (ERP)—and their people—to solve their schedule and capacity load monitoring challenges.

Read MoreTackling a Mold Designer Shortage

Survey findings reveal a shortage of skilled mold designers and engineers in the moldmaking community, calling for intervention through educational programs and exploration of training alternatives while seeking input from those who have addressed the issue successfully.

Read MoreMaking Quick and Easy Kaizen Work for Your Shop

Within each person is unlimited creative potential to improve shop operations.

Read MoreHow to Improve Your Current Efficiency Rate

An alternative approach to taking on more EDM-intensive work when technology and personnel investment is not an option.

Read MoreRead Next

Constraint Management: How to Break a Roadblock

Learning how to get the most out of what your shop has today.

Read MoreThe Secret to Getting On Time and Reducing Leadtimes

Create a competitive advantage by refocusing your job scheduling strategy.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)